The Ancient World - Part 1: The First Civilizations | The History of the...

01 The Seven Wonders of the Ancient World: what were they, and what happened to them? Individually, the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World can be regarded as astounding architectural achievements or marvels of human imagination and engineering – but together, they form an ancient travel guide, there to challenge the limitations of the time and, literally, reach for the skies. Advertisement What are the seven wonders of the world? They consist of a pyramid, a mausoleum, a temple, two statues, a lighthouse and a near-mythical garden – the Great Pyramid of Giza, Mausoleum at Halicarnassus, the Temple of Artemis, the Statue of Zeus, the Colossus of Rhodes, the Lighthouse of Alexandria and the Hanging Gardens of Babylon. Despite only being a short-lived collection – the last to be completed, the Colossus of Rhodes, stood for less than 60 years – and one of them, the Hanging Gardens of Babylon, possibly not existing at all, the Wonders continue to capture imaginations and drive archaeologists and treasure hunters. They laid the foundations for what humans could achieve. Yet for all their fame, there are many questions surrounding these classical creations. Who decided what constituted a ‘Wonder’ in the first place? As Greek travellers explored the conquests of other civilisations, such as the Egyptians, Persians and Babylonians, they compiled early guidebooks of the most remarkable things to see, meant as recommendations for future tourists – which is why the Seven Wonders are all around the Mediterranean Rim. They called the landmarks that bewildered and inspired them theamata (‘sights’), but this soon evolved to the grander name of thaumata – ‘wonders’. Why are there only seven wonders? The Seven Wonders we know today are an amalgamation of all the different lists from antiquity. The best-known versions come from the second-century-BC poet Antipater of Sidon, and mathematician Philo of Byzantium, but other names include Callimachus of Cyrene and the great historian Herodotus. What made their list relied on where they travelled and, of course, their personal opinion, so while we recognise the Lighthouse of Alexandria as a Wonder today, some left it out, favouring the Ishtar Gate of Babylon instead. But why are there only seven? Despite a plethora of structures and statues in the ancient world worthy of inclusion, there have only ever been seven Wonders. The Greeks chose this number as they believed it held spiritual significance, and represented perfection. This may be as it was the number of the five known planets at the time, plus the Sun and Moon. And another question about the Seven Wonders, considering all but one are long lost or destroyed, may be – what exactly are they? 1 Great Pyramid of Giza How the Pyramids of Giza were built remains a subject of debate – but it almost certainly wasn’t built by slaves (Photo by Sipley/ClassicStock/Getty Images) Get a room full of people to name the Seven Wonders and most would name the Great Pyramid of Giza first. The reason is simple enough – while the other six have been lost for centuries, the Great Pyramid of Giza still stands proudly in northern Egypt. Built in c2500 BC as the tomb of the fourth-dynasty pharaoh Khufu, it is the largest of the three Giza pyramids. Its original height of 146.5 metres (481 feet) made the pyramid the tallest human-made structure in the world until Lincoln Cathedral eclipsed it in the 14th century. The years have seen the outer layer of limestone erode – cutting almost eight metres (27 feet) off the height – but the pyramid remains one of the most extraordinary sights on the planet. Recent estimates suggest that it took around 14 years to transport and place the 2.3 million stone blocks. Just how the pyramids were built – or how, 4,000 years ago, Egyptians aligned their structures with the points of the compass – remains the subject of debate. 2 Mausoleum at Halicarnassus The Mausoleum at Halicarnassus, tomb of Mausolus, built 353-350 BC (Photo by Michael Nicholson/Corbis via Getty Images) Over the course of his life, the powerful Mausolus built a magnificent new capital for himself and his wife Artemisia at Halicarnassus (on the western coast of modern-day Turkey), sparing no expense to fill it with beautiful marble statues and temples. There was no question that he, being the satrap (governor) of the Persian Empire and ruler of Caria, would enjoy similar luxury after he died in 353 BC. Artemisia (also Mausolus’s sister) was supposedly so grief-stricken by her husband’s death that she mixed his ashes with water and drank them, before overseeing the building of his extravagant tomb. Made of white marble, the monumental structure sat on a hill overlooking the capital he had built. Artemisia was supposedly so grief-stricken by her husband’s death that she mixed his ashes with water and drank them, before overseeing the building of his extravagant tomb It had been designed by Greek architects Pythius and Satyros and boasted three levels – combining Lycian, Greek and Egyptian architectural styles. The lowest was around 20 metres (66 feet) high, forming a base of steps that led to the second level, ringed by 36 columns. The roof was in the shape of a pyramid, with a sculpture of a four-horse chariot on top bringing the height of the tomb to around 41 metres (135 feet). Four of Greece’s most renowned artists created other sculptures and friezes to surround the tomb, each decorating a single side. The tomb may have been destroyed by earthquakes in medieval times, but a part of it lives on to this day – such was the splendour of Mausolus’s final resting place that his name led to the word ‘mausoleum’. 3 Statue of Zeus The Statue of Zeus towered at almost 12 metres (39 feet) high (Photo by Bettmann/Getty Images) Olympia – a sanctuary in ancient Greece, the site of the first Olympic Games and the home to a Wonder. And what better way to respect the chief god of the Ancient Greeks than to build a giant statue of him? That’s what sculptor Phidias did when he erected his masterpiece at the Temple of Zeus at Olympia, in c435 BC. Zeus sat resplendent on a throne made of cedar wood and decorated with gold, ivory, ebony and precious stones. The god of thunder held a statue of Nike, the goddess of victory, in his outstretched right hand and a sceptre with an eagle perched on top in his left. He was further adorned with gold and ivory, meaning that the temple priests had to oil the statue regularly to protect it from the hot and humid conditions of western Greece. Such was the size of the statue, almost 12 metres (39 feet) high, that it barely fitted inside the temple, with one observing, “It seems that if Zeus were to stand up, he would unroof the temple.” For eight centuries, people would voyage to Olympia just to see the statue. It survived Roman emperor Caligula, who wanted it brought to Rome so that its head could be replaced with his own likeness, but Zeus was eventually lost. It may have happened with the destruction of the temple in AD 426, or been consumed in afire after being transported to Constantinople. Listen: Everything you ever wanted to know about ancient Greece, but were afraid to ask Professor Paul Cartledge responds to listener queries and popular search enquiries about one of the most renowned and influential ancient civilisations in these two episodes of our ‘Everything you wanted to know’ podcast series. 4 Hanging Gardens of Babylon A botanical wonder, but there is no conclusive evidence that the Hanging Gardens of Babylon ever existed (Photo by Bettmann/Getty Images) Detailed descriptions may exist in many ancient texts, both Greek and Roman, but no other Wonder is more mysterious than the Hanging Gardens of Babylon. All accounts, after all, are secondhand, and there is still no conclusive evidence that they existed at all. If they were real, they demonstrated a level of engineering skill way ahead of its time, as keeping a garden lush and alive in the deserts of what is now Iraq would have been no small feat. One theory is that the Babylonian King Nebuchadnezzar II had the Hanging Gardens created, in c600 BC, to help his homesick wife, who missed the greenery of her Median homeland (what is now Iran). Your guide to the ancient city of Babylon On the bank of the Euphrates once lay one of the ancient world’s most powerful cities. Why did it become so famous, and what do we really know about the Tower of Babel? They may have been an ascending series of rooftop gardens, with some of the terraces supposedly reaching a height of around 23 metres (75 feet). This gave the impression of a mountain of flowers, plants and herbs growing out of the heart of Babylon. The exotic vegetation would have been irrigated by a sophisticated system of pumps and pipes, bringing water from the Euphrates river. Philo of Byzantium describes the process of watering the gardens: “Aqueducts contain water running from higher places, partly they allow the flow to run straight downhill and partly they force it up, running backwards, by means of a screw,” which includes an early ‘Archimedes Screw’. “Exuberant and fit for a king is the ingenuity, and most of all, forced, because the cultivator’s hard work is hanging over the heads of the spectators.” It has been postulated that the Hanging Gardens did exist, but not in Babylon. Dr Stephanie Dalley of the University of Oxford claimed that the gardens and irrigation were the creation of the Assyrian king Sennacherib for his palace at Ninevah, 300 miles to the north and on the Tigris river. 5 Lighthouse of Alexandria The Lighthouse of Alexandria as imagined in the 18th century. It was built on the island of Pharos in the bay of Alexandria (Photo by The Print Collector/Getty Images) Boats sailing into the harbour of Alexandria found it a tricky prospect, thanks to shallow waters and rocks. A solution was needed for the thriving Mediterranean port (on the coast of Egypt) – founded by Alexander the Great in 331 BC, hence the name – and it came in the shape of a lighthouse on the nearby island of Pharos. Greek architect Sostratus of Cnidus was handed the job, which took well over a decade, with construction finished in the reign of Ptolemy II, c280-70 BC. It is thought that the lighthouse reached a height a little under 140 metres (459 feet), making it the second-tallest human-made structure of antiquity behind the Great Pyramid of Giza. The tower was divided into a square base, an octagonal midsection and a cylindrical upper section, all connected by a spiral ramp so that a fire could be lit at the top. This was allegedly visible 30 miles away. Greek poet Posidippus described the sight: “This tower, in a straight and upright line, appears to cleave the sky from countless stadiums away… throughout the night, a sailor on the waves will see a great fire blazing from its summit.” This design became the blueprint for all lighthouses since. Like some of the other Seven Wonders, the lighthouse fell victim to earthquakes. It managed to survive several major shocks, but not without heavy damage that led to it being abandoned. The ruins collapsed for good in the 15th century. That wasn’t the last of the lighthouse, however, as French archaeologists discovered massive stones in the waters around Pharos in 1994, which they claim formed part of the ancient structure. Then in 2015, Egyptian authorities announced their intention to rebuild the Wonder. 6 Temple of Artemis The Temple of Artemis was repeatedly destroyed by flood, arson and raids over the centuries (Photo by The Print Collector/Print Collector/Getty Images) You may have an opinion on what was the greatest Wonder, but few were more certain than Antipater of Sidon. His tribute to the Temple of Artemis read: “I have set eyes on the wall of lofty Babylon on which is a road for chariots, and the statue of Zeus by the Alpheus, and the Hanging Gardens, and the colossus of the Sun, and the huge labour of the high pyramids, and the vast tomb of Mausolus but when I saw the house of Artemis that mounted to the clouds, those other marvels lost their brilliancy, and I said, ‘Lo, apart from Olympus, the Sun never looked on aught so grand’.” ...when I saw the house of Artemis that mounted to the clouds, those other marvels lost their brilliancy Antipater of Sidon That said, the temple had a difficult, violent existence, so much so that there were actually several temples, built one after the other in Ephesus, modern-day Turkey. The Wonder was repeatedly destroyed by a seventh-century-BC flood, an arsonist named Herostratus in 356 BC, who hoped to achieve fame by any means, and a raid by the East Germanic Goths in the third century. Its final destruction came in AD 401. Very little remains of the temple, save for fragments held by the British Museum. At its most impressive – the version that inspired Antipater’s account – the white marble temple ran for over 110x55m (361x180ft), with its entire length ornamented by carvings, statues and 127 columns. Inside stood a statue of the goddess Artemis, a site of homage for the many visitors to Ephesus, who left offerings at her feet. 7 Colossus of Rhodes The Colossus of Rhodes stood for less than 60 years (Photo by Bettmann/Getty Images) Erected c282 BC, the Colossus of Rhodes was the last Wonder built, and among the first destroyed. It stood for less than 60 years, but that didn’t signal the end of its status as a Wonder. The mighty statue of the sun god Helios had been erected over 12 years by the sculptor Chares of Lindos to celebrate a military triumph in a year-long siege. Legend claims that the people of Rhodes sold the tools left by their vanquished foe to help pay for the Colossus, melted down abandoned weapons for its bronze and iron edifice, and used a siege tower as scaffolding. Overlooking the harbour, Helios stood at 70 cubits – some 32 metres (105 feet) – high, possibly holding a torch or a spear. Some depictions show him straddling the harbour entrance, allowing ships to sail through his legs, but this would have been impossible with the casting techniques of the time. Regardless, the Colossus still wasn’t strong enough to withstand an earthquake in 226 BC, and the statue came crashing to the ground in pieces. Rhodians declined Ptolemy’s offer to have it rebuilt, having been told by an oracle that they had offended Helios. So the giant, broken sections lay on the ground, where they stayed for over 800 years still attracting visitors. The historian Pliny the Elder wrote: “Even as it lies, it excites our wonder and admiration. Few people can clasp the thumb in their arms, and its fingers are larger than most statues.” When enemy forces finally sold the Colossus for scrap in the seventh century, it took 900 camel loads to shift all the pieces. Jonny Wilkes is a freelance writer specialising in history Advertisement This article was originally published in the October 2016 edition of BBC History Revealed 02 Why Sudan's Remarkable Ancient Civilization Has Been Overlooked by History If you drive north from Khartoum along a narrow desert road toward the ancient city of Meroe, a breathtaking view emerges from beyond the mirage: dozens of steep pyramids piercing the horizon. No matter how many times you may visit, there is an awed sense of discovery. In Meroe itself, once the capital of the Kingdom of Kush, the road divides the city. To the east is the royal cemetery, packed with close to 50 sandstone and red brick pyramids of varying heights; many have broken tops, the legacy of 19th-century European looters. To the west is the royal city, which includes the ruins of a palace, a temple and a royal bath. Each structure has distinctive architecture that draws on local, Egyptian and Greco-Roman decorative tastes—evidence of Meroe’s global connections. Off the highway, men wearing Sudanese jalabiyas and turbans ride camels across the desert sands. Although the area is largely free of the trappings of modern tourism, a few local merchants on straw mats in the sand sell small clay replicas of the pyramids. As you approach the royal cemetery on foot, climbing large, rippled dunes, Meroe’s pyramids, lined neatly in rows, rise as high as 100 feet toward the sky. “It’s like opening a fairytale book,” a friend once said to me. Temple of SolebThe 14th-century B.C. Temple of Soleb was built by Egyptian pharaoh Amenhotep III during a period when Egypt’s reign encompassed ancient Nubia. A strong resemblance to Luxor Temple has led some scholars to suggest that both complexes were built by the same architect. (Matt Stirn)Map of Sudan I first learned of Sudan’s extraordinary pyramids as a boy, in the British historian Basil Davidson’s 1984 documentary series “Africa.” As a Sudanese-American who was born and raised in the United States and the Middle East, I studied the history of ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia, the Levant, Persia, Greece and Rome—but never that of ancient Nubia, the region surrounding the Nile River between Aswan in southern Egypt and Khartoum in central Sudan. Seeing the documentary pushed me to read as many books as I could about my homeland’s history, and during annual vacations with my family I spent much of my time at Khartoum’s museums, viewing ancient artifacts and temples rescued from the waters of Lake Nasser when Egypt’s Aswan High Dam was built during the 1960s and ’70s. Later, I worked as a journalist in Khartoum, Sudan’s capital, for close to eight years, reporting for the New York Times and other news outlets about Sudan’s fragile politics and wars. But every once in a while I got to write about Sudan’s rich and relatively little known ancient history. It took me more than 25 years to see the pyramids in person, but when I finally visited Meroe, I was overwhelmed by a feeling of fulfilled longing for this place, which had given me a sense of dignity and a connection to global history. Like a long lost relative, I wrapped my arms around a pyramid in a hug. The land south of Egypt, beyond the first cataract of the Nile, was known to the ancient world by many names: Ta-Seti, or Land of the Bow, so named because the inhabitants were expert archers; Ta-Nehesi, or Land of Copper; Ethiopia, or Land of Burnt Faces, from the Greek; Nubia, possibly derived from an ancient Egyptian word for gold, which was plentiful; and Kush, the kingdom that dominated the region between roughly 2500 B.C. and A.D. 300. In some religious traditions, Kush was linked to the biblical Cush, son of Ham and grandson of Noah, whose descendants inhabited northeast Africa. Inside a pyramid tomb at MeroeInside a pyramid tomb at Meroe that some archaeologists believe belonged to Kushite King Tanyidamani. The tomb, adorned with Egyptian-style relief carvings, dates to the second century B.C. (Matt Stirn)The largest pyramid at El-KurruThe largest pyramid at El-Kurru, built around 325 B.C, once stood 115 feet tall. Only its base remains today after it was disassembled during the medieval era to build a nearby fortification wall. (Matt Stirn) For years, European and American historians and archaeologists viewed ancient Kush through the lens of their own prejudices and that of the times. In the early 20th century, the Harvard Egyptologist George Reisner, on viewing the ruins of the Nubian settlement of Kerma, declared the site an Egyptian outpost. “The native negroid race had never developed either its trade or any industry worthy of mention, and owed their cultural position to the Egyptian immigrants and to the imported Egyptian civilization,” he wrote in an October 1918 bulletin for Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts. It wasn’t until mid-century that sustained excavation and archaeology revealed the truth: Kerma, which dated to as early as 3000 B.C., was the first capital of a powerful indigenous kingdom that expanded to encompass the land between the first cataract of the Nile in the north and the fourth cataract in the south. The kingdom rivaled and at times overtook Egypt. This first Kushite kingdom traded in ivory, gold, bronze, ebony and slaves with neighboring states such as Egypt and ancient Punt, along the Red Sea to the east, and it became famous for its blue glazed pottery and finely polished, tulip-shaped red-brown ceramics. Among those who first challenged the received wisdom from Reisner was the Swiss archaeologist Charles Bonnet. It took 20 years for Egyptologists to accept his argument. “Western archaeologists, including Reisner, were trying to find Egypt in Sudan, not Sudan in Sudan,” Bonnet told me. Now 87, Bonnet has returned to Kerma to conduct field research every year since 1970, and has made several significant discoveries that have helped rewrite the region’s ancient history. He identified and excavated a fortified Kushite metropolis nearby, known as Dukki Gel, which dates to the second millennium B.C. Inside the tomb of King TantamaniInside the tomb of King Tantamani, circa 650 B.C, in El-Kurru, the site of royal burials during Egypt’s 25th Dynasty, when Kush conquered Egypt and initiated the reign of the “Black Pharaohs.” (Matt Stirn)Egyptian-style relief carvings, dates to the second century B.C.Inside a pyramid tomb at Meroe that some archaeologists believe belonged to Kushite King Tanyidamani. The tomb, adorned with Egyptian-style relief carvings, dates to the second century B.C. (Matt Stirn) Around 1500 B.C., Egypt’s pharaohs marched south along the Nile and, after conquering Kerma, established forts and temples, bringing Egyptian culture and religion into Nubia. Near the fourth cataract, the Egyptians built a holy temple at Jebel Barkal, a small flat-topped mountain uniquely situated where the Nile turns southward before turning northward again, forming the letter “S.” It was this place, where the sun is born from the “west” bank—typically associated with sunset and death—that ancient Egyptians believed was the source of Creation. Egyptian rule prevailed in Kush until the 11th century B.C. As Egypt retreated, its empire weakening, a new dynasty of Kushite kings rose in the city of Napata, about 120 miles southeast of Kerma, and asserted itself as the rightful inheritor and protector of ancient Egyptian religion. Piye, Napata’s third king, known more commonly in Sudan as Piankhi, marched north with an army that included horsemen and skilled archers and naval forces that sailed north on the Nile. Defeating a coalition of Egyptian princes, Piye established Egypt’s 25th Dynasty, whose kings are commonly known as the Black Pharaohs. Piye recorded his victory in a 159-line inscription in Middle Egyptian hieroglyphics on a stele of dark gray granite preserved today in the Egyptian Museum in Cairo. He then returned to Napata to rule his newly expanded kingdom, where he revived the Egyptian tradition, which had been dormant for centuries, of entombing kings in pyramids, at a site called El-Kurru. Tent camps in the Bayuda DesertIn addition to traditional hotels, tourism companies offer immersive experiences in the Bayuda Desert, allowing travelers to sleep in tent camps like this one, seen at sunrise. (Matt Stirn)Fallen statue of a Kushite kingA statue of a Kushite king near Tombos, not far from Kerma, which served as an Egyptian colonial settlement before Kush re-established control over Nubia. The statue retains mystical significance for nearby villagers, who visit for blessings to help with fertility and childbirth. (Matt Stirn)local boy Near El-Kurru, a local boy waits for hibiscus tea to serve customers at a roadside teahouse along the remote desert highway connecting Khartoum to Cairo. (Matt Stirn) One of Piye’s sons, Taharqa, known in Sudan as Tirhaka, was mentioned in the Hebrew Bible as an ally of Jerusalem’s King Hezekiah. He moved the royal cemetery to Nuri, 14 miles away, and had a pyra-mid built for himself that is the largest of those erected to honor the Kushite kings. Archaeologists still debate why he moved the royal cemetery. Geoff Emberling, an archaeologist at the University of Michigan who has excavated at El-Kurru and Jebel Barkal, told me that one explanation focusing on Kushite ritual is that Taharqa situated his tomb so that “the sun rose over the pyramid at the moment when the Nile flooding is supposed to have arrived.” But there are other explanations. “There might have been a political split,” he said. “Both explanations might be true.” The Black Pharaohs’ rule of Egypt lasted for nearly a century, but Taharqa lost control of Egypt to invading Assyrians. Beginning in the sixth century B.C., when Napata was repeatedly threatened by attack from Egyptians, Persians and Romans, the kings of Kush gradually moved their capital south to Meroe. The city, at the junction of several important trade routes in a region rich in iron and other precious metals, became a bridge between Africa and the Mediterranean, and it grew prosperous. “They took on influences from outside—Egyptian influences, Greco-Roman influences, but also influences from Africa. And they formed their very own ideas, their own architecture and arts,” says Arnulf Schlüter, of the State Museum of Egyptian Art in Munich. The Nubian Rest HouseThe Nubian Rest House, near Jebel Barkal. For years, Kushite sites throughout Sudan remained little visited, but the overthrow of authoritarian President Omar al-Bashir energized a nascent tourism industry. (Matt Stirn)A nomadic familyA nomadic family prepares to set off into the Bayuda Desert, in the eastern Sahara. In Kushite times, a caravan route through this desert connected Napata in the north to Meroe in the south. (Matt Stirn) The pyramids in Meroe, which was named a Unesco World Heritage site in 2011, are undoubtedly the most striking feature here. While they are not as old or as large as the pyramids in Egypt, they are unique in that they are steeper, and they were not all dedicated to royals; nobles (at least those who could afford it) came to be buried in pyramids as well. Many Sudanese today are quick to point out that the number of standing ancient pyramids in the country—more than 200—exceeds the number of those in Egypt. Across from the pyramids is the royal city, with surrounding grounds that are still covered in slag, evidence of the city’s large iron-smelting industry and a source of its economic power. Queens called by the title Kandake, known in Latin as “Candace,” played a vital role in Meroitic political life. The most famous of them was Amanirenas, a warrior-queen who ruled Kush from roughly 40 B.C. to 10 B.C. Described by the Greek geographer Strabo, who mistook her title for her name, as “a masculine sort of woman, and blind in one eye,” she led an army to fight off the Romans to the north and returned with a bronze statue head of Emperor Augustus, which she then buried in Meroe beneath the steps to a temple dedicated to victory. In the town of Naga, where Schlüter does much of his work, another kandake, Amanitore, who ruled from about 1 B.C. to A.D. 25, is portrayed beside her co-regent, King Natakamani, on the entrance-gate wall of a temple dedicated to the indigenous lion god Apedemak; they are depicted slaying their enemies—Amanitore with a long sword, Natakamani with a battle-ax—while lions rest symbolically at their feet. Many scholars believe that Amanitore’s successor, Amantitere, is the Kushite queen referred to as “Candace, queen of the Ethiopians” in the New Testament, whose treasurer converted to Christianity and traveled to Jerusalem to worship. Sufi graves of KermaSufi graves from the 17th century near the medieval city of Old Dongola. The style of the burials, adorned with white pebbles and marked by black stones, can be traced to the pre-Islamic city of Kerma, from the third millennium B.C., indicating the continuity of Nubian ritual traditions. (Matt Stirn)A fort built by Ottoman forces near the Nile RiverA fort built by Ottoman forces near the Nile River’s third cataract, not far from Tombos and Kerma. Ottoman Egypt conquered much of modern Sudan in 1820, which it ruled until 1885. (Matt Stirn) At another site not far away, Musawwarat es-Sufra, archaeologists still wonder about the purpose that a large central sandstone complex, known as the Great Enclosure, might have served. It dates to the third century B.C., and includes columns, gardens, ramps and courtyards. Some scholars have theorized that it was a temple, others a palace or a university, or even a camp to train elephants for use in battle, because of the elephant statues and engravings found throughout the complex. There is nothing in the Nile Valley to compare it to. By the fourth century A.D., the power of Kush began to wane. Historians give different explanations for this, including climate change-driven drought and famine and the rise of a rival civilization in the east, Aksum, in modern-day Ethiopia. For years, Kush’s history and contributions to world civilization were largely ignored. Early European archaeologists were unable to see it as more than a reflection of Egypt. Political instability, neglect and underdevelopment in Sudan prevented adequate research into the country’s ancient history. Yet the legacy of Kush is important because of its distinctive cultural achievements and civilization: it had its own language and script; an economy based on trade and skilled work; a well-known expertise in archery; an agricultural model that allowed for raising cattle; and a distinctive cuisine featuring foods that reflected the local environment, such as milk, millet and dates. It was a society organized differently from its neighbors in Egypt, the Levant and Mesopotamia, with unique city planning and powerful female royals. “At its height, the Kingdom of Kush was a dominant regional power,” says Zeinab Badawi, a distinguished British-Sudanese journalist whose documentary series “The History of Africa” aired on the BBC earlier this year. Kush’s surviving archaeological remains “reveal a fascinating and uncelebrated ancient people the world has forgotten.” Tent camp at sunriseIn addition to traditional hotels, tourism companies offer immersive experiences in the Bayuda Desert, allowing travelers to sleep in tent camps like this one, seen at sunrise. (Matt Stirn) While Egypt has long been explained in light of its connections to the Near East and the Mediterranean, Kush makes clear the role that black Africans played in an interconnected ancient world. Kush was “at the root of black African civilizations, and for a long time scholars and the general public berated its achievements,” Geoff Emberling told me. Edmund Barry Gaither, an American educator and director of Boston’s Museum of the National Center of Afro-American Artists, says that “Nubia gave black people their own place at the table, even if it did not banish racist detractors.” The French archaeologist Claude Rilly put it to me this way: “Just as Europeans look at ancient Greece symbolically as their father or mother, Africans can look at Kush as their great ancestor.” Today, many do. In Sudan, where 30 years of authoritarian rule ended in 2019 after months of popular protests, a new generation is looking to their history to find national pride. Among the most popular chants by protesters were those invoking Kushite rulers of millennia past: “My grandfather is Tirhaka! My grandmother is a Kandake!” Intisar Soghayroun, an archaeologist and a member of Sudan’s transitional government, says that rediscovering the country’s ancient roots helped fuel the calls for change. “The people were frustrated with the present, so they started looking into their past,” she told me. “That was the moment of revolution.” 03 WORLD-CLASS VENUES ANNOUNCED FOR THE AIG WOMEN’S OPEN THROUGH TO 2025 19 August 2020, Troon, Scotland: The R&A has underlined its commitment to enhancing the AIG Women’s Open’s status as a leading major sporting event by announcing five world-class venues for championships being played from 2021 to 2025.The future championship venues for the AIG Women’s Open are: 2021 – Carnoustie 2022 – Muirfield 2023 – Walton Heath 2024 – St Andrews 2025 – Royal Porthcawl Martin Slumbers, Chief Executive of The R&A, said, “With our partners at AIG, we have a real ambition to grow and elevate the AIG Women's Open for the benefit of the world's leading golfers and so we are excited to confirm our intention to play the next five championships at these renowned courses. “It has truly been a collaborative effort from all the venues involved to make this schedule possible and the flexibility that they have shown in adjusting their own calendars has been vital in allowing us to confirm our plans for the championship through to 2025. “We are grateful for their support, particularly during a time when golf has been impacted by the on-going pandemic, and we look forward to working with these venues to deliver an outstanding experience to be enjoyed by everyone involved in the AIG Women’s Open.” Peter Zaffino, President and Global Chief Operating Officer, AIG, commented, “AIG is pleased to partner with The R&A to increase visibility and engagement in women’s professional golf by enhancing the global stature of the AIG Women’s Open. We proudly welcome the involvement of these venerable courses, which will be fitting hosts for these accomplished golfers as they compete at the highest level.” Muirfield, Walton Heath and Royal Porthcawl will be hosting the women’s major championship for the first time. Muirfield has a prestigious history of hosting major championships, having held The Open on 16 occasions. It also hosted The Curtis Cup in 1952 and 1984 as well as the Vagliano Trophy in 1963 and 1975. Walton Heath has been a venue for the Ryder Cup, the Senior Open presented by Rolex and the British Masters. Royal Porthcawl has held The Amateur Championship on seven occasions and was the venue for the Walker Cup in 1995 when Great Britain and Ireland defeated a United States of America team featuring Tiger Woods. It has also hosted the Senior Open presented by Rolex, the Curtis Cup and the British Masters. The Old Course at St Andrews will stage the championship for the third time after Lorena Ochoa and Stacy Lewis won the title over the world famous links in 2007 and 2013. The AIG Women’s Open will return to Carnoustie for the first time since 2011 when Yani Tseng successfully defended her title. The AIG Women’s Open will take place from 16-22 August 2021 at Carnoustie with tickets now on sale via aigwomensopen.com. Adult tickets will start from £20 with children aged 16 years or under before the Championship admitted free of charge. Spectators aged 24 years or under will be entitled to purchase youth (16-24 years) tickets. A £5 Mastercard discount is available per transaction. All future championship dates will be announced in due course. For more ticket and championship information please visit aigwomensopen.com.

01

02

03

The 14th-century B.C. Temple of Soleb was built by Egyptian pharaoh Amenhotep III during a period when Egypt’s reign encompassed ancient Nubia. A strong resemblance to Luxor Temple has led some scholars to suggest that both complexes were built by the same architect. (Matt Stirn)

The 14th-century B.C. Temple of Soleb was built by Egyptian pharaoh Amenhotep III during a period when Egypt’s reign encompassed ancient Nubia. A strong resemblance to Luxor Temple has led some scholars to suggest that both complexes were built by the same architect. (Matt Stirn)

Inside a pyramid tomb at Meroe that some archaeologists believe belonged to Kushite King Tanyidamani. The tomb, adorned with Egyptian-style relief carvings, dates to the second century B.C. (Matt Stirn)

Inside a pyramid tomb at Meroe that some archaeologists believe belonged to Kushite King Tanyidamani. The tomb, adorned with Egyptian-style relief carvings, dates to the second century B.C. (Matt Stirn) The largest pyramid at El-Kurru, built around 325 B.C, once stood 115 feet tall. Only its base remains today after it was disassembled during the medieval era to build a nearby fortification wall. (Matt Stirn)

The largest pyramid at El-Kurru, built around 325 B.C, once stood 115 feet tall. Only its base remains today after it was disassembled during the medieval era to build a nearby fortification wall. (Matt Stirn) Inside the tomb of King Tantamani, circa 650 B.C, in El-Kurru, the site of royal burials during Egypt’s 25th Dynasty, when Kush conquered Egypt and initiated the reign of the “Black Pharaohs.” (Matt Stirn)

Inside the tomb of King Tantamani, circa 650 B.C, in El-Kurru, the site of royal burials during Egypt’s 25th Dynasty, when Kush conquered Egypt and initiated the reign of the “Black Pharaohs.” (Matt Stirn) Inside a pyramid tomb at Meroe that some archaeologists believe belonged to Kushite King Tanyidamani. The tomb, adorned with Egyptian-style relief carvings, dates to the second century B.C. (Matt Stirn)

Inside a pyramid tomb at Meroe that some archaeologists believe belonged to Kushite King Tanyidamani. The tomb, adorned with Egyptian-style relief carvings, dates to the second century B.C. (Matt Stirn) In addition to traditional hotels, tourism companies offer immersive experiences in the Bayuda Desert, allowing travelers to sleep in tent camps like this one, seen at sunrise. (Matt Stirn)

In addition to traditional hotels, tourism companies offer immersive experiences in the Bayuda Desert, allowing travelers to sleep in tent camps like this one, seen at sunrise. (Matt Stirn) A statue of a Kushite king near Tombos, not far from Kerma, which served as an Egyptian colonial settlement before Kush re-established control over Nubia. The statue retains mystical significance for nearby villagers, who visit for blessings to help with fertility and childbirth. (Matt Stirn)

A statue of a Kushite king near Tombos, not far from Kerma, which served as an Egyptian colonial settlement before Kush re-established control over Nubia. The statue retains mystical significance for nearby villagers, who visit for blessings to help with fertility and childbirth. (Matt Stirn) Near El-Kurru, a local boy waits for hibiscus tea to serve customers at a roadside teahouse along the remote desert highway connecting Khartoum to Cairo. (Matt Stirn)

Near El-Kurru, a local boy waits for hibiscus tea to serve customers at a roadside teahouse along the remote desert highway connecting Khartoum to Cairo. (Matt Stirn) The Nubian Rest House, near Jebel Barkal. For years, Kushite sites throughout Sudan remained little visited, but the overthrow of authoritarian President Omar al-Bashir energized a nascent tourism industry. (Matt Stirn)

The Nubian Rest House, near Jebel Barkal. For years, Kushite sites throughout Sudan remained little visited, but the overthrow of authoritarian President Omar al-Bashir energized a nascent tourism industry. (Matt Stirn) A nomadic family prepares to set off into the Bayuda Desert, in the eastern Sahara. In Kushite times, a caravan route through this desert connected Napata in the north to Meroe in the south. (Matt Stirn)

A nomadic family prepares to set off into the Bayuda Desert, in the eastern Sahara. In Kushite times, a caravan route through this desert connected Napata in the north to Meroe in the south. (Matt Stirn) Sufi graves from the 17th century near the medieval city of Old Dongola. The style of the burials, adorned with white pebbles and marked by black stones, can be traced to the pre-Islamic city of Kerma, from the third millennium B.C., indicating the continuity of Nubian ritual traditions. (Matt Stirn)

Sufi graves from the 17th century near the medieval city of Old Dongola. The style of the burials, adorned with white pebbles and marked by black stones, can be traced to the pre-Islamic city of Kerma, from the third millennium B.C., indicating the continuity of Nubian ritual traditions. (Matt Stirn) A fort built by Ottoman forces near the Nile River’s third cataract, not far from Tombos and Kerma. Ottoman Egypt conquered much of modern Sudan in 1820, which it ruled until 1885. (Matt Stirn)

A fort built by Ottoman forces near the Nile River’s third cataract, not far from Tombos and Kerma. Ottoman Egypt conquered much of modern Sudan in 1820, which it ruled until 1885. (Matt Stirn) In addition to traditional hotels, tourism companies offer immersive experiences in the Bayuda Desert, allowing travelers to sleep in tent camps like this one, seen at sunrise. (Matt Stirn)

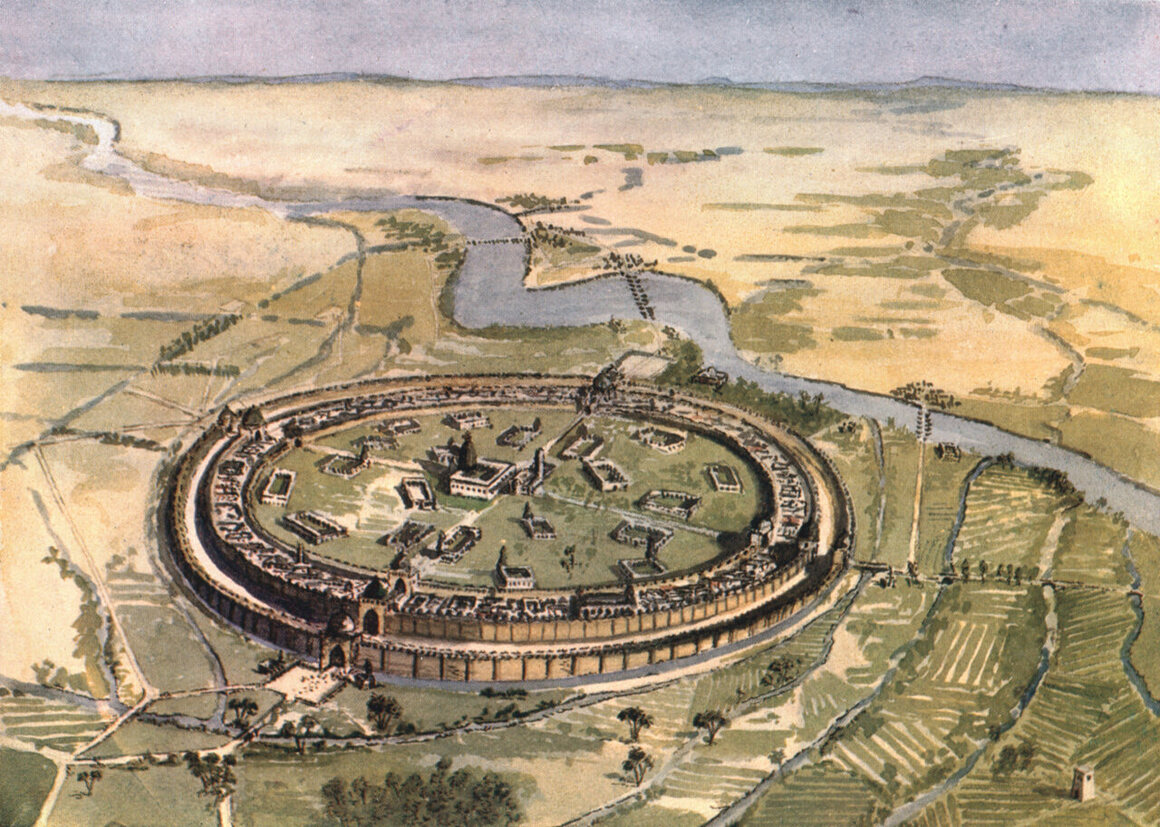

In addition to traditional hotels, tourism companies offer immersive experiences in the Bayuda Desert, allowing travelers to sleep in tent camps like this one, seen at sunrise. (Matt Stirn) A 1915 painting by Edmund Sandars depicting Baghdad as it would have appeared in the eighth century, in the days of Abu Jafar al-Mansur. The Print Collector/Heritage Images via Getty Images

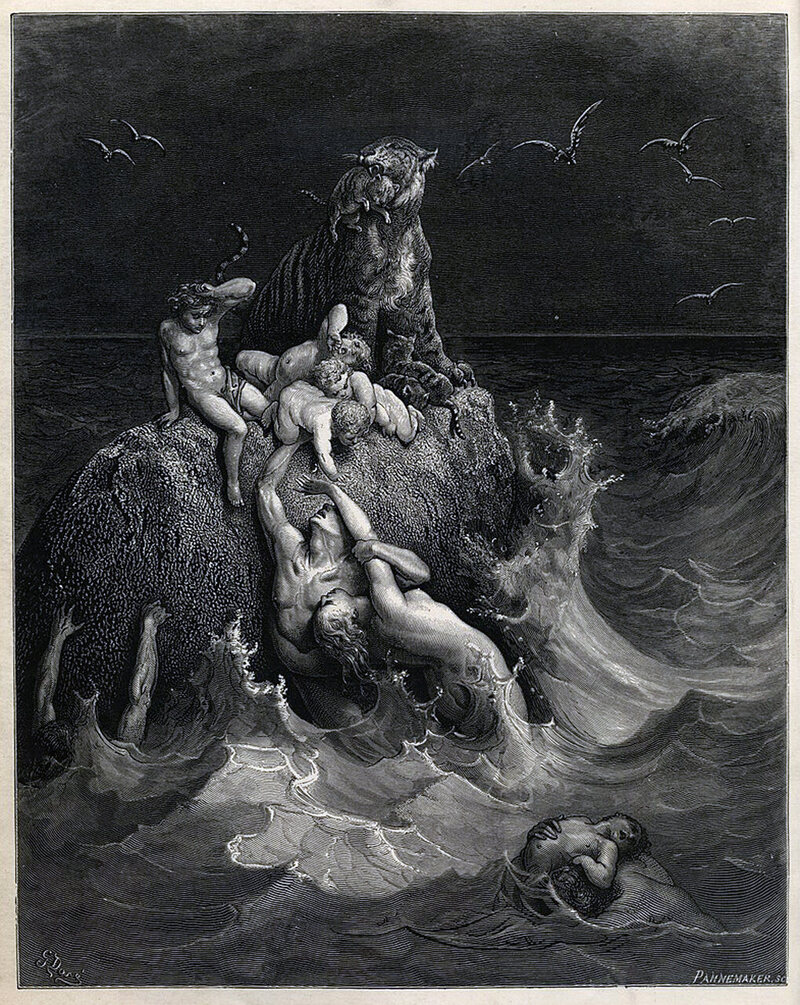

A 1915 painting by Edmund Sandars depicting Baghdad as it would have appeared in the eighth century, in the days of Abu Jafar al-Mansur. The Print Collector/Heritage Images via Getty Images The Deluge, the frontispiece to Gustave Doré’s illustrated edition of the Bible, depicting the Great Flood. Public domain

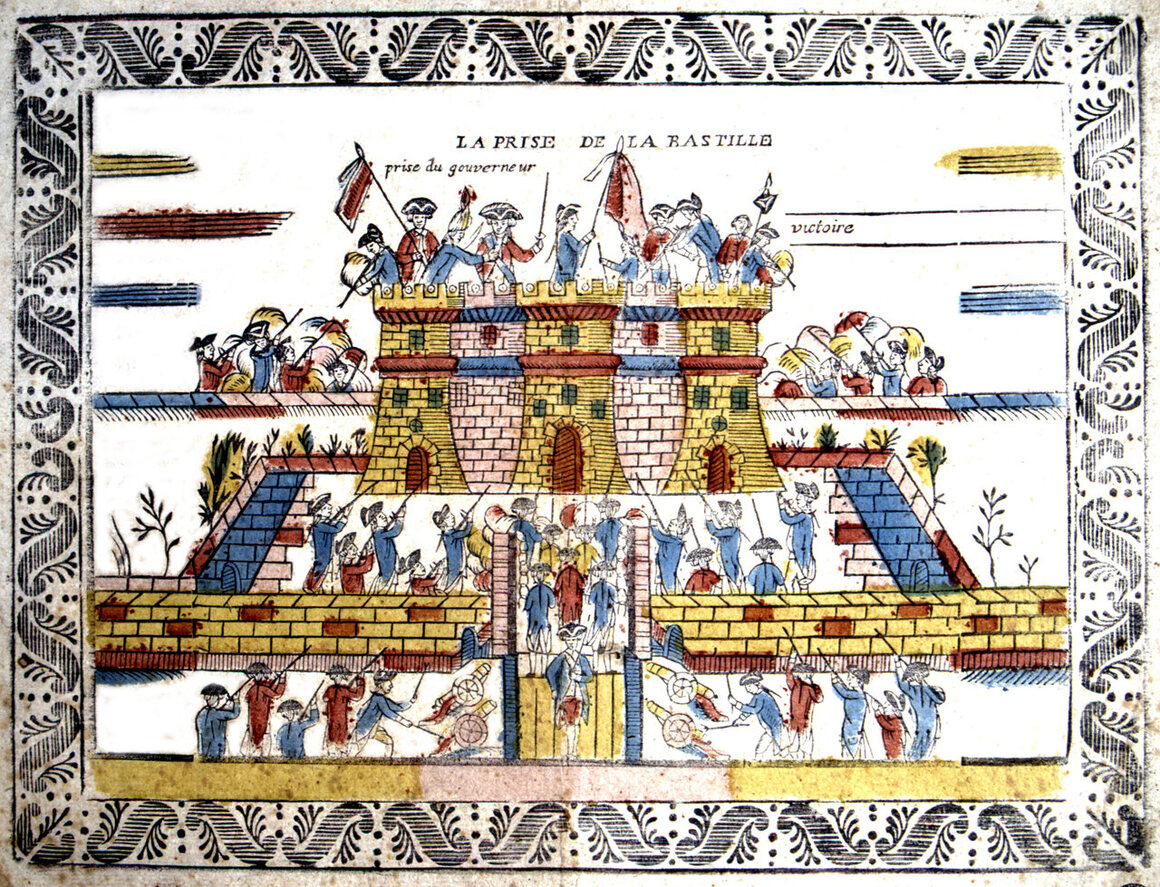

The Deluge, the frontispiece to Gustave Doré’s illustrated edition of the Bible, depicting the Great Flood. Public domain An illustration of the Storming of the Bastille during the French Revolution in 1789. Photo12/UIG/Getty Images

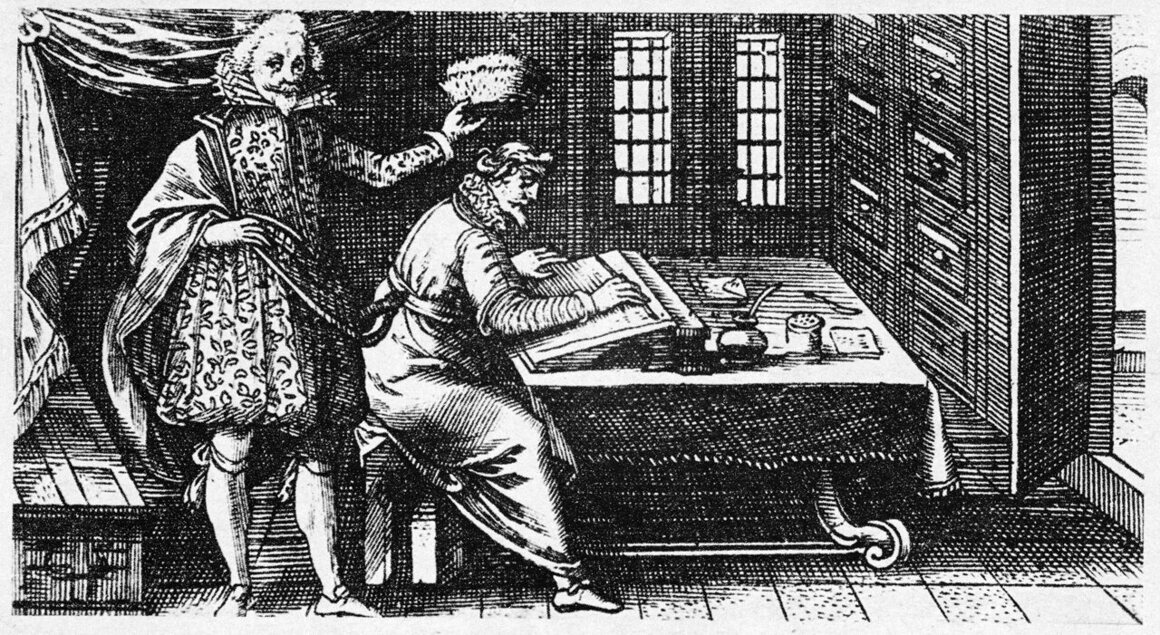

An illustration of the Storming of the Bastille during the French Revolution in 1789. Photo12/UIG/Getty Images An allegorical engraving, from 1941, illustrating William Shakespeare doffing his “cap of maintenance” in honor of Francis Bacon, who some believe was the true author of the Bard’s works. Roger Viollet Collection/Getty Images

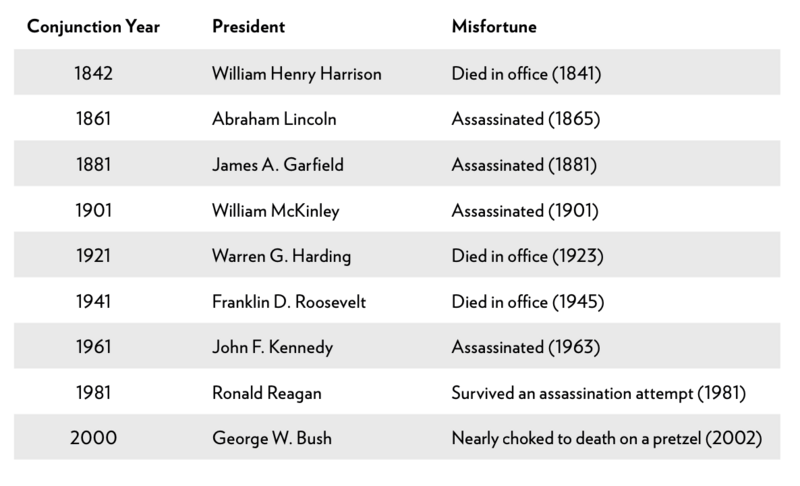

An allegorical engraving, from 1941, illustrating William Shakespeare doffing his “cap of maintenance” in honor of Francis Bacon, who some believe was the true author of the Bard’s works. Roger Viollet Collection/Getty Images Jupiter-Saturn conjunctions appear to be harbingers of presidential deaths in office, assassinations, or near-death mishaps. New York Yankees’ championships follow a similar pattern. Courtesy Alexander Boxer

Jupiter-Saturn conjunctions appear to be harbingers of presidential deaths in office, assassinations, or near-death mishaps. New York Yankees’ championships follow a similar pattern. Courtesy Alexander Boxer

Comments

Post a Comment

If you have any doubt, please let me know....